I was working at Mass. Eye and Ear, one of the country’s foremost ophthalmology hospitals, when a partial eclipse occurred on August 21, 2017. It was mildly interesting to see the sun partially obscured: we used glasses to view the spectacle safely, looked through a pinhole in a cereal box, and took some amateur photos with our phones.

It was an amusing diversion to get us out of the office for an hour, and certainly seeing the sun take on a Pac-Man shape was unprecedented — the last total solar eclipse to cross the United States was in February 1979, which predated my arrival on this planet.

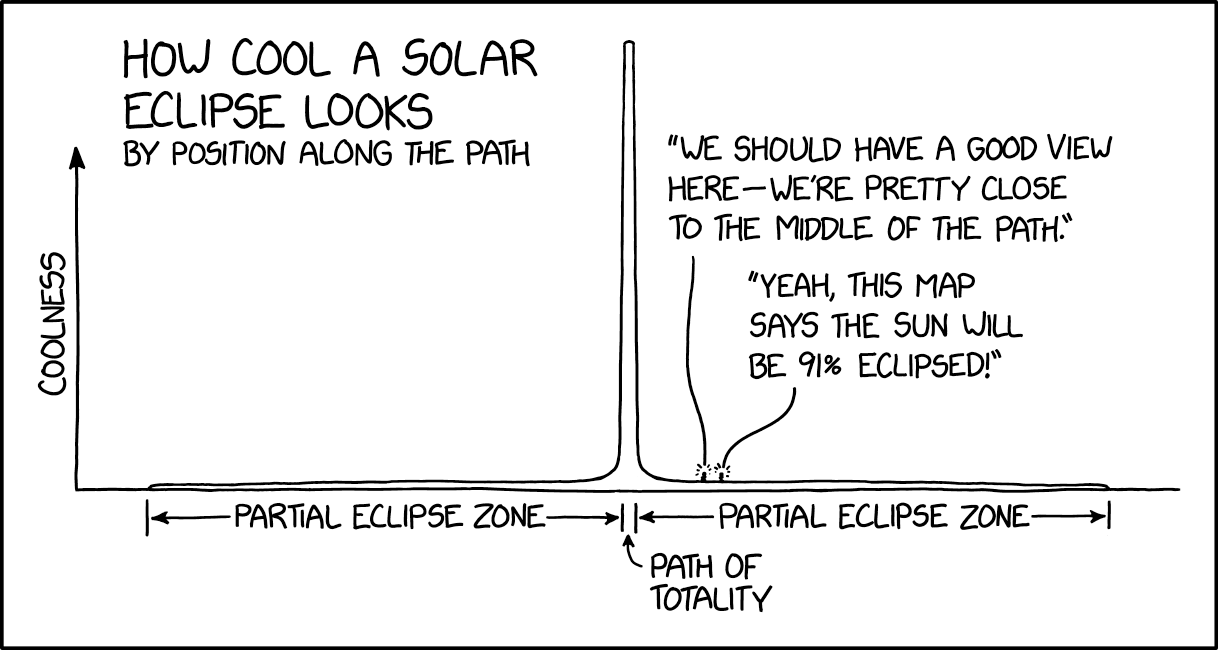

As soon as the 2017 eclipse was over, a Facebook event popped up for the next one: the Great North American Eclipse of April 8, 2024, seven years away. Knowing how rare eclipses are, I immediately RSVPed in the affirmative to remind myself: even if what I saw in 2017 was underwhelming, I wanted to give it another chance in 2024. Except that time, I would put myself in the path of totality: the moon would boldly obstruct the entire sun, unlike in a partial eclipse, where it makes only a halfhearted attempt before giving up.

Seven years later, come this past January, I was ready to book an Airbnb in Burlington, Vermont. I didn’t realize that eclipse fever had filled the city’s reservations months or years in advance, leaving the pickings slim. Fortunately, most eclipse chasers show up only for the occasion before turning around, making only a brief visit to the area; as a nomad, I stay in my destinations for much longer, making me an attractive guest to most Airbnb proprietors. Finding a pad with a five-night minimum stay was easy, and I booked it for three weeks on either side of the eclipse.

Forecast

After moving to Burlington, I realized the city holds a dubious honor: it’s tied with Seattle for the most cloudy days in the country. Most eclipse-chasers were setting their sights on Texas, where they were likelier to get a clear view. It didn’t bode well for us New Englanders.

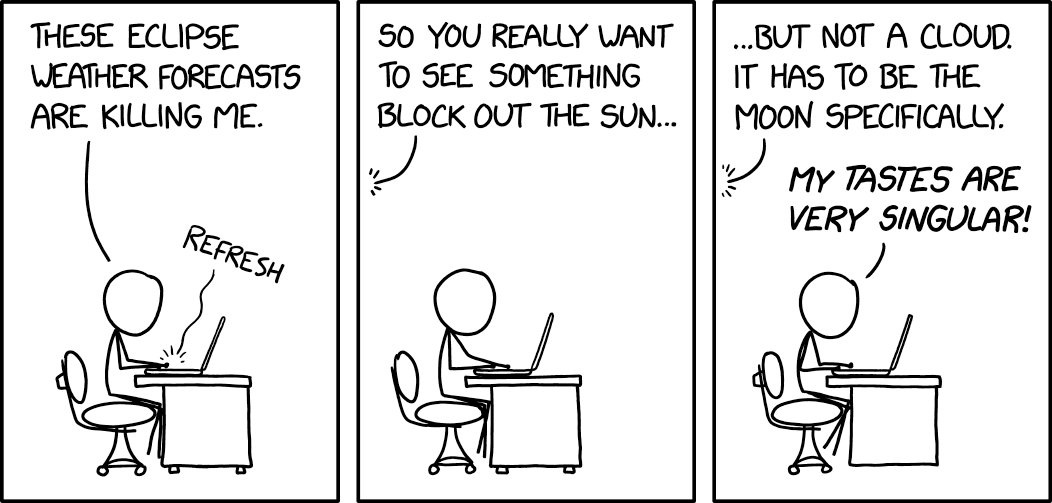

For almost two weeks straight, I kept refreshing the long-term forecast. As we got closer to April 8, the prediction started looking better — and better — and better! Ultimately, northern New England became one of the best places in the country to view the eclipse.

My fortune came at others’ misfortune: storms and clouds brewed across the rest of the United States, ruining the view for millions of others. A few of those solar enthusiasts ditched their plans, made years earlier, and diverted to Vermont, increasing what was already a massive influx of visitors. The city of Burlington has a population of 42,500, yet over 70,000 people came to town for the eclipse. The population of the entire state of Vermont is only 625,000, which increased by 200,000 for the occasion.

Among those visitors was my youngest brother and his daughter, who drove three hours to Burlington the night before the eclipse. The next morning, my friend Jess and her two friends drove up from Boston. On Monday, we six convened in Battery Park, a short 15-minute walk from my Airbnb.

The wait

Battery Park was filled with visitors and residents from across the country and the spectrum. Some set up lawn chairs; others did handstands; still others tossed frisbees to their dogs. A band played in the park, competing with another band we could see below us in Waterfront Park.

When the eclipse began, I saw a sight familiar from seven years ago: larger and larger slices of the sun disappearing behind the moon. I tried to capture the waning gibbous sun with my iPhone 13 mini, its camera shielded behind eclipse glasses, but unsurprisingly, the result was mediocre at best; pocket-sized consumer devices just aren’t designed to capture celestial events.

By contrast, Jess had an impressive photography rig consisting of a Sony Alpha 7R IV camera and Sony G Master 100-400mm lens mounted on a tripod with a Star Adventurer 2i that automatically tracked the position of the sun. The camera was set to snap a photo every 2.5 seconds, saving them onto two high-speed 128GB SD cards. Due to its automated nature, we wouldn’t see the photos until the next day.

The eclipse

In a partial eclipse, this bite that’s taken out of the sun slowly fills back in, and then it’s over. But with this total eclipse, the bite kept getting bigger and bigger. For 72 minutes, the sky got darker, and the temperature dropped by as much as 15º Fahrenheit.

Sometimes the progress of the eclipse was so subtle as to be invisible to the naked eye. But when just a sliver of sun — a “diamond ring” — was left, the sun’s final disappearance was noticeable in real time.

Eclipse glasses, which are needed during partial eclipses but not total ones, are funny things: they don’t block just the sun’s harmful radiation; they block everything but the sun. The entire world becomes a black, blank slate with the exception of one yellow dot in the sky. Once the moon slid entirely in front of the sun, my glasses showed nothing anywhere. I removed my glasses to better see what I assumed would be an empty sky.

I could not have been more wrong.

Blazing in the sky above us was an impossible, otherworldly sight: an angry sun, raging to be seen from behind a brazen moon. What had been a sliver of light mere moments earlier was now a fiery black hole, white light erupting from beyond the event horizon. All the science fact and fiction I’d consumed throughout my life could not have prepared me for this spectacle.

My mind was as frozen as the first time I went skydiving, utterly unable to comprehend what it was witnessing. “What is happening??” I shouted repeatedly as I looked around, looking for anyone as bewildered as I was. For once, my brother was as shocked as I was. I accidentally took a selfie, capturing for eternity our dumbfoundedness.

I slowly got some wits about me. I looked down at my bright red shirt, as well as a handful of Skittles a stranger had given me earlier, to see if the colors looked more muted — something known as the Purkinje effect. It was barely noticeable. I wasted further precious seconds trying to snap some photos of the eclipse with my iPhone; again, the pictures were terrible. I briefly observed that the horizon looked like a sunset, matching the dusk that had fallen across the park. Later, I realized that the harmless honey bees that had been buzzing nearby had all gone dormant, having grounded themselves under the sudden blanket of darkness.

The band was quiet. The park was quiet. Everything was quiet. Until finally, three minutes and fourteen seconds later, an assertive sun revealed another diamond ring, and the crowd cheered for what we had all shared. The sun waxed, and we donned again our glasses.

Jess later compiled her thousands of individual photos into a time-lapse video. The moment the sky broke occurs at 2:17.

The next eclipse

Near the end of the back half of the eclipse, my family started their drive home; Jess and her passengers departed soon after. They joined the throngs of visitors who began a simultaneous exodus, turning highways into parking lots: what should’ve been a three-hour drive lasted nine.

My recovery was just as prolonged. For many hours after the eclipse was over, I crashed hard, like one does at the end of a party or convention, when all their friends have gone home; they’re sad the event is over and that they won’t get to see each other again for a long time. My sense of loss wasn’t for those I’d spent the day with, but for the eclipse itself.

I’d lacked a presence, a mindfulness, during my first solar eclipse — and I’m okay with that. The only way it could’ve played out any differently was if my mind had been less blown, and I would not have traded that feeling of overwhelm for anything.

But the whole experience had lasted less than four minutes, which wasn’t enough. To put it another way: only 0.00001481% of my life had been spent inside a total eclipse. I needed it to be more than that. I wouldn’t see another eclipse for a long time — but I needed to.

When I got home, I tried to make a Facebook event for the next solar eclipses over the United States: August 23, 2044 (visible only from Montana and the Dakotas) and August 12, 2045 (visible from California to Florida). But Facebook now allows events to be scheduled only two years in advance, a technical limitation that only served to underscore how many decades away I was from having this experience again — how long I’d have to wait, if I’d even be here, before seeing another total eclipse.

But just as the sun had slowly dawned again that afternoon, so too did awareness: I’d limited myself to the next eclipses to occur in the United States — but eclipses occur across the globe with much greater frequency than that. Some brief research determined that there are 28 eclipses in the next 42 years, with the next one being only two years from now in Spain. And with the life of a digital nomad, it’s almost trivial for me to ensure I’m in the right place at the right time.

The partial eclipse I saw in Boston is incomparable to what I experienced last week in Burlington. That perfect moment of totality is a transcendent event comparable only to itself. I will never again see my first solar eclipse — but I know I haven’t seen my last.

Ken, I completely agree with your sense of “shock” at totality. One important note – we saw the total eclipse in 2017 and it was indeed awesome. However, with time, the event faded, perhaps because we were so surprised at what we were seeing. Last week we saw the total eclipse from Ohio, and it was even more awe inspiring the second time around. So even though you say that you’ll never again see your first eclipse, for some reason it seemed to be even better the second time. Maybe because your brain is more aware and can just enjoy the spectacle even more?

Thanks for that note of encouragement, Chris! I look forward to seeing my first second eclipse. 😎

We were camping near Broken Bow Oklahoma (you know, where Klingons first made contact with humans) for the eclipse. We also woke up to very cloudy skies, but literally 5 minutes before the totality began, the clouds parted, and we had a fantastic view of the whole thing. As you said — it was awe-inspiring.

BTW, hope you’re enjoying Burlington. It’s one of my favorite towns, having gone to college there and working there for 8 years.

I was at a car dealership getting something with more tech help. They were stunned by the eclipse. As it was also my second (Larry and I went north for the one mid-1990s), I was at least whelmed enough to jump up and down a little. What no one I spoke with realized was that the new moon was at 2:19 p.m. EDT that day, so we wouldn’t have really noticed the moon without its passage in front of its big brother. Glad you got to enjoy – and freak out a little – because of it.